The Tragedy of Baby Deaths – A Story of Inequality

The heartbreak of losing a child to stillbirth or death soon after birth is utterly devastating. In the UK we tend to think of birth as a safe process leading to a happy outcome, yet stillbirths and neonatal deaths do occur here.

Racism at the root

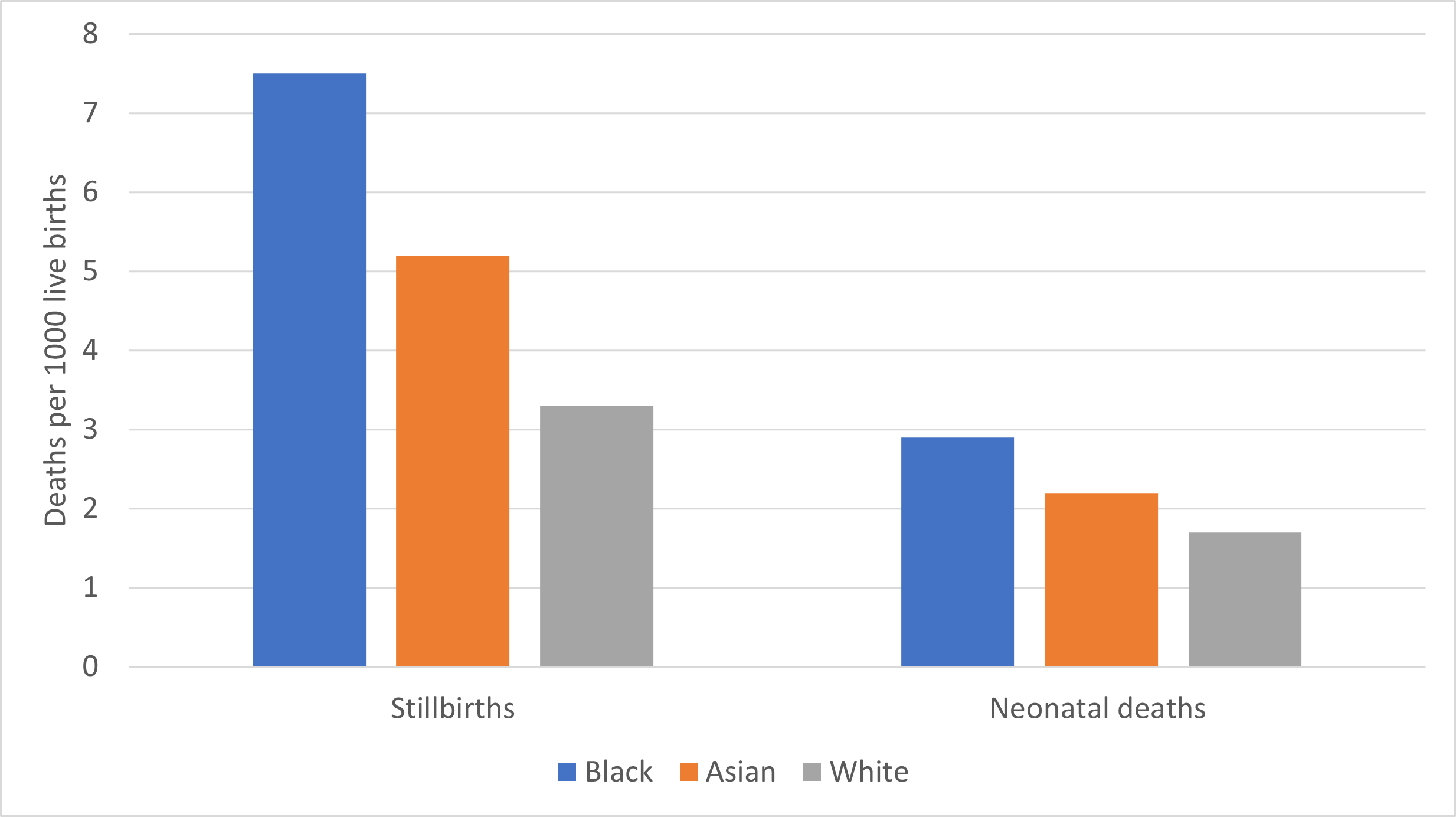

Babies of Black ethnicity have the highest rates of both stillbirth and baby death, with babies of Asian origin also experiencing higher rates of both these outcomes than white babies (1).

Stillbirth and neonatal deaths by ethnicity

Figure 1: Stillbirth and neonatal deaths (in first month of life) per 1,000 live births by ethnicity (MBRRACE data 2021)

Source: MBRRACE data for 2021 (3)

Black women are twice as likely to have a stillbirth as white women

Particularly high perinatal mortality rates are also found in Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities as well as among refugees and undocumented migrants, who face specific barriers to maternal health care.

Inequalities extend to maternal deaths

This inequity is even more severe when it comes to maternal deaths: There is an almost four-fold difference in maternal mortality rates amongst women from Black ethnic backgrounds and an almost two-fold difference amongst women from Asian ethnic backgrounds compared to white women (4).

At root is systemic racism:

Sandra Igwe, Maternal Health Advocate

Poverty a key factor

In addition to race, poverty is a key factor in baby deaths. Women living in deprived areas have more stillbirths and baby deaths than those in wealthier areas. These factors come together with the result that Black and Asian women in the poorest areas have far greater rates of stillbirth and baby deaths than white women in the richest areas.

Underlying factors in ethnic and poverty inequalities

The physiological biomedical reasons for these inequalities are many and varied, but they include increased rates of maternal smoking, obesity and behavioural factors (5). Other broader environmental and social factors such as exposure to pollution, poor housing, and less access to maternity care and health care in general are also part of the picture, as well as the chronic stress caused by economic strain, insecure employment and more frequent stressful life events. The COVID-19 pandemic made things worse.

With specific regard to ethnicity, recent review by NHS Race and Health Observatory found widespread evidence of poor communication between health care providers and women of colour. This is made a great deal worse by a lack of interpreting services (6). Yet even when language was not a factor, women’s health care was often undermined by a lack of trust and culturally insensitive behaviour. Black and Asian women consistently reported stereotyping, disrespect, and discrimination.

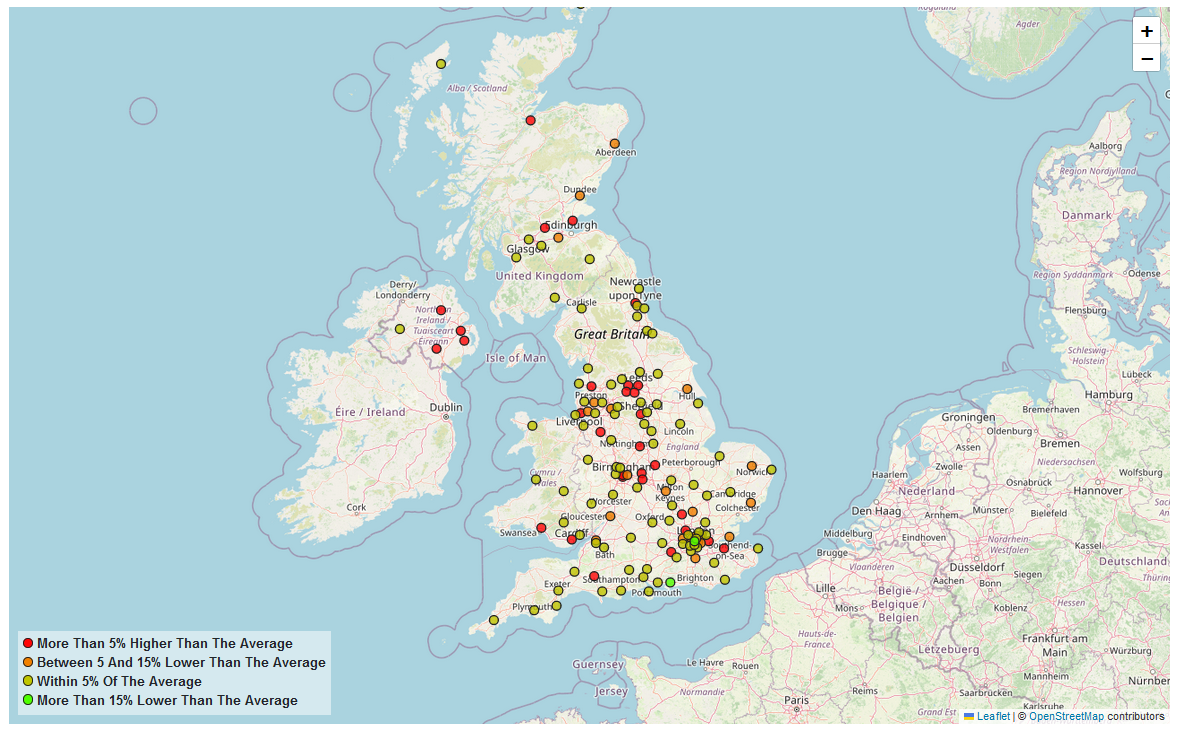

Unexplained differences between health care providers

While the differences in death rates at provider level demonstrated in the map will at least partly be explained by underlying ethnic and socio-economic factors, MMBRACE also adjust their data to account for both the level of care provided and underlying risk factors of the population (including age, ethnicity and poverty) (8). These data still show marked differences between similarly grouped trusts, that may indicate differences in quality of care. These are demonstrated in our map, which provide ratings of newborn and stillbirths compared to the average across similar trusts (please see map for further information on how MBRRACE calculate their indicators).

Responding to inequalities in neonatal deaths and stillbirths

Despite the long-standing and compelling evidence of inequalities in stillbirths and baby deaths, successive UK Governments have failed to invest in understanding and reducing them. Instead, the focus has been on individual behaviours such as smoking, or on identifying ‘at risk’ babies through better monitoring of poor fetal growth. While these biomedical interventions can be beneficial, they fail to address key underlying factors.

Cultural competence

The now widespread evidence of institutional racism and discrimination calls for a renewed focus on culturally competent care. This means services which are sensitive to people's cultural identity and which are responsive to people’s beliefs or conventions. Key to this is staff education, but this needs to go beyond routine teaching about cultural practices; education needs to challenge wider issues of power imbalance and unconscious bias. Staff operate in an environment that wither supports or limits culturally appropriate practices. Institutional level approaches such as increasing the number of staff from minority groups, improving the accessibility and quality of translation services and making practical changes to the healthcare environment have also been successful in improving women’s experience and their uptake of services.

A critical element of culturally competent care is developing greater links with communities to increase trust in the maternity services, through involvement of local community leaders and third sector organisation. This can include co-creation of services to meet the needs of marginalised groups.

Katie Bonful, in ‘My Black Motherhood’, by Sandra Igwe (9).

Other approaches to reducing inequities

Midwife-led continuity of care reduces preterm birth and overall fetal mortality, as does community-based antenatal care, in turn reducing the risk of women ‘falling through the gaps’ in health care.

Multisectoral approaches are essential, given that deprivation and poverty are important factors. Policy makers and practitioners must work with agencies that provide housing and other community services to enhance care for women living in complex circumstance. These interventions must apply across people’s life course, as disadvantage can be both cumulative and intergenerational.

Collection of data on ethnicity needs to be improved to understand inequalities. Measurement of poverty and deprivation is currently mostly limited to data at the area level so again greater data capturing individual disadvantage is required. The UK also needs to develop standard indicators disaggregated by ethnicity and deprivation to monitor inequalities in access to care.

Inequality targets

While the Government has set ambitious targets to reduce baby deaths and stillbirths by 50%, it has no targets to reduce inequalities. Governments should set targets for reducing disparities in these health outcomes and ask the Care Quality Commission to specifically consider them.

Reference links

- State of the Nation Report | MBRRACE-UK (le.ac.uk)

- RHO-Rapid-Review-Final-Report_Summary_v.4.pdf (nhsrho.org)

- MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_2021_-_Lay_Summary_v10.pdf (ox.ac.uk)

- State of the Nation Report | MBRRACE-UK (le.ac.uk)

- Adverse pregnancy outcomes attributable to socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in England: a national cohort study - The Lancet

- RHO-Rapid-Review-Final-Report_Summary_v.4.pdf (nhsrho.org)

- https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/hnn-content/uploads/Respectful-Maternity-Care-Charter-2019.pdf

- State of the Nation Report | MBRRACE-UK (le.ac.uk)

- Igwe, Sandra. My Black Motherhood: Mental Health, Stigma, Racism and the System. United Kingdom: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2022.

Click here to view the Perinatal data

Click here to view the Perinatal data