The Mental Health Of Mothers – A Tale of Inequalities

Mental ill-health causes untold suffering to women during pregnancy and the first year after having a baby. Suicide is now a leading cause of death for mothers between six weeks and 12 months after they give birth. (1)

Sandra Igwe, ‘My Black Motherhood; Mental Health, Stigma, Racism and the System’. (2)

The scale of the problem

From 10% to 20% of all women are affected to some extent by poor mental health during pregnancy or after birth. (3) However, severe problems increased dramatically during the COVID lockdowns. In 2020, women were three times more likely to die by suicide (during pregnancy or up to six weeks after birth) compared to 2017-19. (4) Left untreated, mental ill-health can also have significant and long-lasting effects on the woman, her child, and her wider family. Meanwhile there are gross inequalities in maternal mental health services across the UK, and particular groups such as adolescents and women from ethnic minorities face specific barriers in accessing care.

Solutions

We do know what works in supporting mothers with mental ill-health:

- Firstly they must be promptly identified by their maternity care providers or other health care staff.

- Secondly, women identified with mental health needs must have prompt support.

- Thirdly, while there are a range of providers that can support the mental health of pregnant women and new mothers in the community, women with severe mental health problems need support from specialist perinatal mental health (PMH) services.

PMH services include specialist community teams and inpatient Mother and Baby Units for when hospitalisation is needed. They can offer advice for planning a pregnancy to women with mental health needs and provide parent-infant support.

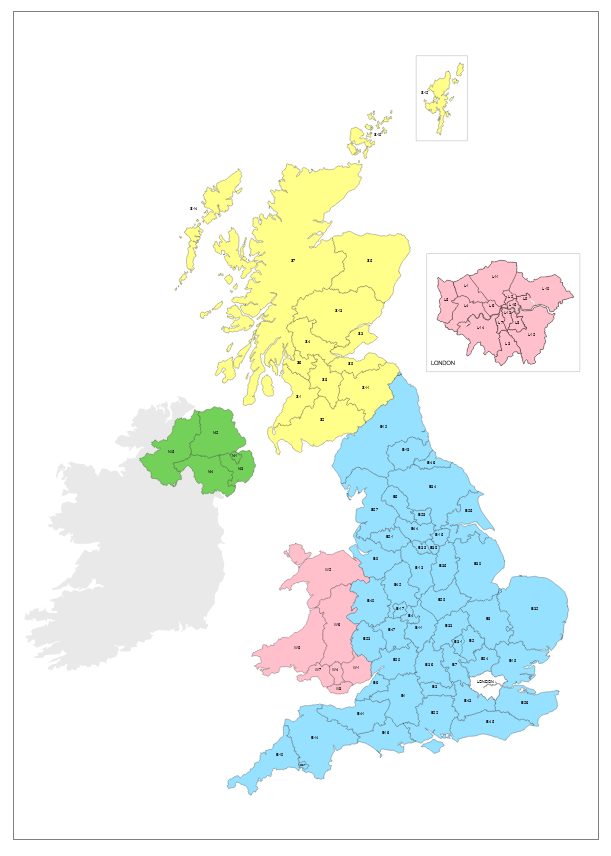

Inequalities of location: the ‘postcode lottery’

Every woman should have access to these services for up to two years after the birth of a child. In January 2016, Prime Minister David Cameron announced investment to ensure UK-wide access to PMH services including specialist community services and psychiatric inpatient mother and baby units.

However, these services are still a ‘postcode lottery’.

Maps produced by the Maternal Mental Health Alliance in 2022 suggest the majority of English Health Trusts reach the basic standards defined by the Royal College of Psychiatry with regards to patient safety, rights, dignity, the law and fundamentals of care, including the provision of evidence-based care and treatment. (5)

However, only 14% of Scottish Health Boards and no Boards in Wales or Northern Ireland have met these standards. In Scotland and Northern Ireland there are some Health Boards with no multidisciplinary team support for the perinatal period.

There are still only 21 Mother and Baby Units throughout the whole of the UK, severely limiting this vital service to much of the population. There are none at all in Northern Ireland.

Inequalities of race

Race is a major factor in the inequalities experienced by pregnant women and mothers in need of mental health care.

This plays out through language barriers, and also through cultural, social and financial factors.

Not only do women from Black African, Asian and White Other backgrounds face greater barriers in accessing services in the community than White British women, they are also more likely to be detained in hospital (involuntary admission) for severe problems requiring urgent treatment. (6)

Sandra Igwe, Maternal Health Advocate

At an event hosted by the Motherhood Group, many mothers came forward with the particularities and concerns of Black motherhood. Here are a few examples:

From ‘My Black Motherhood; Mental Health, Stigma, Racism and the System’. (2)

Inequalities of age and neurodiversity

Age is further factor in inequalities of service provision. Adolescents are more at risk of perinatal mental health problems, yet they may fall through the gaps between Child and Adolescent services, and PMH services. (7)

Furthermore, the needs of women with neurodiversity, or with personality disorders, substance use problems or learning difficulties, are more often unmet. (8)

Paternal mental health

The biggest killer of men under 50 in the UK is suicide, and fathers with mental health problems during the perinatal period are up to 47 times more likely to be classed as a suicide risk than at any other time in their lives. (9) Health professionals and perinatal mental health services need a better understanding of the resources that fathers need to support both their own mental health and that of their partner.

From ‘Fathers Reaching Out – Why Dads Matter’, by Mark Williams’ (10)

CALL TO ACTION

The UK has made significant progress in rolling out PMH services, but there is still much to do.

We must get better at listening to women, including those from vulnerable and ethnic minority groups. Women’s voices must be heard and fed into the development of responsive and equitable services. In addition we need:

- More and better care: High quality specialist perinatal health services must be provided in all areas of the UK.

- More funding: This must be sustainable and transparent.

- More staff: Recruitment and retention of skilled and trained staff is urgently needed.

- Focus on disadvantaged women: PMH services must be more culturally acceptable, including translation services, as well as being accessible and suitable for women with complex needs

- More data on inequalities: We need robust monitoring to highlight inequalities in care between different groups of women and women in different geographical areas, mapping PMH services in order to end the postcode lottery.

Reference links

- Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care | MBRRACE-UK | NPEU (ox.ac.uk)

- Igwe, Sandra. My Black Motherhood: Mental Health, Stigma, Racism and the System. United Kingdom: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2022.

- Barriers to accessing mental health services for women with perinatal mental illness: systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies in the UK | BMJ Open

- Rising rates of perinatal suicide | The BMJ

- mmha-specialist-perinatal-mental-health-services-uk-maps-2023.pdf

- Differences in access and utilisation of mental health services in the perinatal period for women from ethnic minorities—a population-based study | BMC Medicine | Full Text (biomedcentral.com).

- The maternal mental health experiences of young mums | Maternal Mental Health Alliance

- college-report-cr232---perinatal-mental-heath-services.pdf (rcpsych.ac.uk)

- Risk of suicide and mixed episode in men in the postpartum period - PubMed (nih.gov)

- mark_williams_fathers_reaching_out_pmh_report10_sep_2020_2.pdf (menshealthforum.org.uk)

Click here to view the Mental Health data

Click here to view the Mental Health data